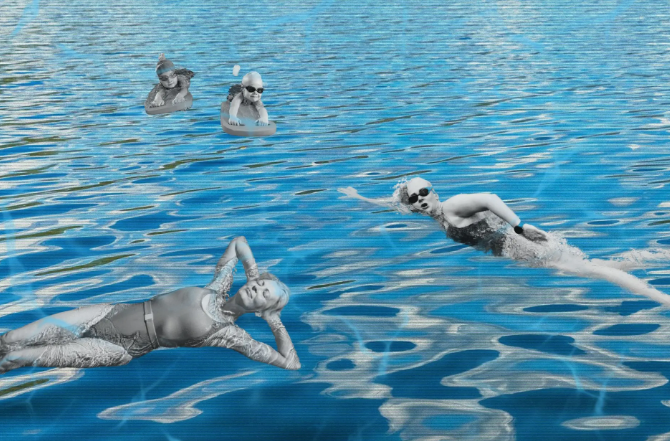

As summer temperatures rise and natural swimming holes beckon, health experts are urging caution before diving into lakes, rivers, and creeks. While these scenic spots may appear pristine, they often harbor unseen health hazards that can cause serious illness.

“Swimming is a great, fun activity,” said Bill Sullivan, a professor of microbiology at Indiana University School of Medicine. “But you do need to be mindful that there are dangers that lurk out there.”

The primary threat? Microscopic organisms—bacteria, viruses, and parasites—that thrive in warm, untreated water. Common culprits include E. coli and Salmonella, typically introduced through fecal contamination from livestock or wildlife. After a heavy rain, runoff can carry waste into swimming areas, increasing the risk of infection.

“If you end up with E. coli or Salmonella, you could experience potentially severe gastrointestinal symptoms—sometimes bad enough to require hospitalization,” Sullivan warned.

Other common threats include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacteria that causes swimmer’s ear, and viruses like rotavirus and norovirus, which cause rapid-onset diarrhea and vomiting. Parasites such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia, shed by cattle or wildlife, can lead to prolonged gastrointestinal distress, especially in vulnerable populations like children, the elderly, or those with weakened immune systems.

Though rare, more serious infections have also been reported. Naegleria fowleri, often dubbed the “brain-eating amoeba,” can be deadly if it enters the body through the nose. Meanwhile, flesh-eating bacteria such as Vibrio vulnificus have increased with warming waters, particularly in saltwater or brackish environments.

Rachel Noble, a water quality expert at the University of North Carolina, said inland swimming locations are harder to monitor than popular coastal beaches. “It’s hard to know where people are going to try to jump in,” she said, adding that state and local health departments often provide online resources and updates on water safety.

To reduce risk, experts recommend checking local water quality reports, avoiding swimming after heavy rains, and staying out of water that looks cloudy, smells foul, or shows signs of algae or runoff.

Sullivan also advises against swallowing water and recommends rinsing off after swimming. “Sanitize or wash your hands before eating or drinking, especially after you’ve been in natural water,” he said.

If symptoms like fever, severe diarrhea, or vomiting occur after a swim, health professionals urge people to seek medical attention—especially if symptoms last more than a few days or include signs of dehydration.

“Swimming outside can be safe and refreshing,” said Sullivan. “But it’s always better to be informed before you dive in.”