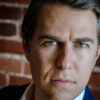

A recent study from Northwestern University has revealed that your bathroom may be home to a diverse range of viruses—far more than expected. Researchers investigated two everyday bathroom items, toothbrushes and showerheads, to see what kinds of microscopic lifeforms might be lurking on their surfaces. The results were surprising, according to Erica Hartmann, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern, who led the study.

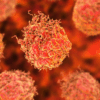

“We found an incredible amount of diversity, which highlights how little we know about the microbial world around us,” Hartmann said. Despite this diversity, most of the viruses identified were bacteriophages, a type of virus that specifically targets bacterial cells, not human cells. While scientists have known about bacteriophages for nearly a century, their understanding of these viruses is still evolving.

The findings, published on October 9 in Frontiers in Microbiomes, add to a growing body of research on the microscopic organisms that populate our everyday environments. Hartmann explained that while bacteriophages don’t pose any threat to human health, their potential as tools in medicine is significant. “Phages are fascinating and represent the next frontier in microbiology,” she noted. Researchers are already exploring ways to use phages in antimicrobial therapies, which could lead to alternatives to traditional antibiotics, especially as antibiotic resistance continues to be a major concern.

This latest study was inspired by an earlier one in which Hartmann’s team explored bacteria found in bathrooms, addressing concerns that bacteria from toilet flushes could contaminate toothbrushes. In that study, they concluded that most of the bacteria found on toothbrushes originated from people’s mouths. This time, however, the focus shifted to viruses, and the team found an unexpectedly rich array of bacteriophages on both toothbrushes and showerheads.

Despite the abundance of these viruses, Hartmann reassured the public that there’s no need for concern. “I don’t think anything in our results gives reason to be worried,” she said. “There is absolutely nothing to suggest people should throw out their toothbrushes.”

The study opens up new possibilities for future research, especially in the field of phage therapy, which uses bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections. Hartmann added, “The more we learn about phages, the better equipped we will be to understand and develop new therapies.”

Ultimately, Hartmann emphasized that the presence of these viruses should be seen as a curiosity rather than a threat. “It’s important to approach the microbes around us with wonder rather than fear,” she said.