A 13-year-old boy’s sudden neck swelling led doctors to uncover an unexpected diagnosis: iodine deficiency. This once-common issue had largely disappeared in the U.S. after the widespread use of iodized salt in the 20th century. However, recent shifts in diet and food manufacturing have raised concerns about a small but growing number of iodine deficiency cases, especially among children and pregnant women.

Iodine, a trace element found in seawater and certain soils, is essential for thyroid function and brain development. When iodine levels are too low, the thyroid gland enlarges in an attempt to compensate, resulting in a condition known as goiter. Although iodine deficiency was common in the U.S. early in the 20th century, it significantly decreased after the introduction of iodized salt in 1924. By the 1950s, more than 70% of U.S. households used iodized salt, and iodine deficiency became rare.

But experts have noted a recent decline in iodine levels. Processed foods, which make up a large part of the American diet, often contain salt that isn’t iodized. Popular salt alternatives like kosher salt and Himalayan rock salt, which lack iodine, are also contributing to the issue. In the case of the 13-year-old boy, who has mild autism and a restricted diet, his intake of iodized salt was minimal, contributing to his deficiency.

Dr. Elizabeth Pearce of Boston Medical Center, a leader in the Iodine Global Network, highlighted a significant drop in U.S. iodine levels between the 1970s and the 1990s. A study showed a 50% decrease in iodine levels in surveyed Americans, sparking concerns about the broader public health implications.

While most Americans still get enough iodine through their diet, experts worry about pregnant women and children, who are especially vulnerable. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends 150 micrograms of iodine daily for pregnant and breastfeeding women, which can be obtained from iodized salt or supplements. However, recent research shows a rise in mild iodine deficiency among pregnant women. A study in Lansing, Michigan, found that a quarter of pregnant women were not getting enough iodine, in part because many prenatal vitamins lack the essential nutrient.

Iodine deficiency during pregnancy can lead to developmental issues, including language delays and lower IQ in children. While some studies have raised concerns, experts caution that more research is needed to understand the long-term effects of iodine deficiency in the U.S. population.

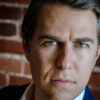

Dr. Monica Serrano-Gonzalez, who treated the boy in Providence, Rhode Island, expressed concern about the rising number of cases in children with restricted diets. She and her colleagues have seen several other iodine deficiency cases and stress the importance of increasing awareness of the issue, especially for vulnerable populations.