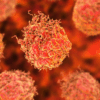

A diagnosis of human papillomavirus (HPV) can understandably cause concern, but experts say it’s important not to panic. While HPV is often linked to several types of cancer, a diagnosis doesn’t automatically mean you have—or will develop—cancer.

Dr. Kathleen Schmeler, a professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, stresses that HPV is extremely common. “Approximately 80% of people are infected with it at some point in their lives,” Schmeler says, adding that most people will clear the virus without even knowing they had it. Even among those who don’t clear it, the vast majority won’t go on to develop cancer.

HPV is often discovered during routine screenings, such as a Pap test for women, which checks for signs of cervical cancer. Men can also contract HPV, though they often don’t realize it unless they develop genital warts. Currently, there are no clinical guidelines for HPV testing in men.

There are over 300 types of HPV, and while most are harmless, some strains pose a higher risk. HPV types 16 and 18 are linked to a range of cancers, including those of the cervix, vagina, penis, anus, and head and neck. Other strains, like types 6 and 11, are considered low-risk and typically cause genital warts rather than cancer.

HPV is spread through sexual contact, including vaginal, oral, and anal sex. Dr. Brinda Emu from Yale School of Medicine notes that HPV infections often peak among individuals under 25 and those over 45, when new sexual partners may increase the risk of transmission.

For women, a positive HPV test result doesn’t necessarily indicate infidelity. “HPV can remain dormant for years before reactivating,” says Dr. Sarah Kim, division director of gynecologic oncology at Penn Medicine.

If diagnosed, follow-up testing is crucial. Dr. Emu explains that an HPV diagnosis isn’t cause for alarm, but it does signal the need for further screening to assess potential risks. If the high-risk types (16 or 18) are present, doctors may monitor the patient more closely, particularly if they are over 30, immunocompromised, or smokers. The good news is that most HPV infections clear up on their own within two years.

If an HPV infection persists, further procedures like a colposcopy may be recommended to look for precancerous cells, which can be treated before they develop into cancer. According to Dr. Amanda Fader, a professor at Johns Hopkins, cervical cancer is preventable with regular screening and early intervention.

While there is no cure for HPV, the vaccine can help prevent future infections. Dr. Rachel Katzenellenbogen, an expert in HPV research, recommends the vaccine for young people before they become sexually active, though it is also available for individuals up to age 45. Even if you’ve been diagnosed with HPV, the vaccine may still offer protection against other strains.

If you’re concerned about HPV or have recently been diagnosed, it’s important to discuss your next steps with your doctor, who can guide you through the process and help manage your risk.