Five years have passed since the COVID-19 pandemic first upended daily life, leaving behind a staggering toll. Since 2020, the virus has claimed over 1.2 million American lives—more than any other country—and accounted for more than one in seven reported COVID-19 deaths worldwide. While some have attempted to downplay the severity of the crisis, history tells a different story. COVID-19 ranks among the deadliest infectious disease outbreaks in human history, trailing only the 1918 Spanish Flu and the Bubonic Plague.

Today, lockdowns and quarantines feel like a distant memory, but the long-term effects—physical, mental, and societal—remain. However, as the world moves forward, an urgent question lingers: Is the U.S. better prepared for the next pandemic?

The troubling answer appears to be no.

Pandemics Are Not a Thing of the Past

The assumption that pandemics occur only once in a lifetime is misleading. In 2009, the H1N1 swine flu pandemic spread worldwide, causing up to half a million deaths. Today, H5N1 bird flu is circulating among poultry, wild birds, and even mammals in the U.S., raising concerns that it could mutate to spread efficiently among humans. Other viruses with pandemic potential—including MERS, Ebola, and mpox—continue to pose threats. And then there’s “Disease X,” the term used to describe an unknown pathogen that could emerge in the future, as COVID-19 did in late 2019.

Despite these risks, the U.S. has been scaling back, rather than strengthening, its pandemic preparedness.

Declining Investments in Public Health

One of the most significant setbacks has been the reduction of U.S. contributions to the World Health Organization (WHO), an essential player in detecting and containing infectious disease outbreaks before they spread. The U.S. previously allocated around $120 million annually for pandemic prevention and emergency response, but recent cuts have created a funding gap. In addition, reductions in support for agencies like USAID are affecting global efforts to combat diseases such as tuberculosis, potentially reversing progress in infectious disease control.

At the national level, de-prioritizing infectious disease research and reducing funding for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) training programs have left the public-health workforce under-resourced. While some staff cuts have been reversed, the loss of experienced professionals who played a key role during COVID-19 could weaken the country’s response to future threats.

A Shift Toward a Hands-Off Approach?

Beyond funding cuts, concerns are growing over the ideology of those positioned to shape public-health policy in the coming years. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has a long history of spreading vaccine misinformation, recently gave a lukewarm endorsement of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine amid a measles outbreak in Texas—despite his past opposition to COVID-19 vaccines. Meanwhile, reports indicate that the Trump administration is reconsidering nearly $600 million in funding for H5N1 mRNA vaccine research, a critical tool in preventing future flu pandemics.

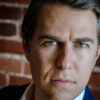

Another potential policy shift comes with Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, who is expected to lead the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Bhattacharya has previously advocated for a herd-immunity approach to COVID-19, a stance that mainstream scientists warned could have resulted in countless preventable deaths. While it is widely acknowledged that some pandemic-era policies—such as prolonged school closures—were flawed, an overly hands-off response in the face of future health emergencies could prove equally harmful.

The Importance of Restoring Trust in Science

Perhaps one of the most significant challenges moving forward is the erosion of public trust in science and health institutions. Misinformation during the pandemic led to widespread skepticism about vaccines, health guidelines, and the intentions of public-health officials. This distrust has been further fueled by rhetoric from high-profile political figures and social media influencers, who have characterized scientific institutions as corrupt or incompetent.

Research from the past five years has shown that trust in health authorities is a key factor in determining whether people follow public-health guidance. The question now is whether the new administration can rebuild that trust. If public confidence in science continues to decline, the ability to effectively manage future health crises will be severely compromised.

A Critical Crossroads

As the world reflects on five years of living with COVID-19, the lessons learned—or ignored—will shape the response to future pandemics. While the crisis exposed weaknesses in public health infrastructure, it also demonstrated the power of science, cooperation, and rapid innovation.

Whether the U.S. strengthens its preparedness or retreats from it remains to be seen. But history has made one thing clear: pandemics are not a matter of if, but when. The choices made today will determine how the country fares when the next outbreak inevitably arrives.